On a cool night in May 2015, our fifteen-year-old son, Finn, went missing for three hours. For most parents of teenagers, this wouldn’t be cause for alarm. But Finn is autistic, has no friends, isn’t a wanderer. Until he was thirteen, he panicked if I was on a different floor of the house. He had gone with his dad, Craig, and younger brother, Reid, to watch the impromptu Victoria Day fireworks in the park we live next to in downtown Toronto. When Craig announced he had to take Reid home to bed – it was a school night – the fireworks were still going, so Finn asked if he could stay out longer. Given Finn’s ironclad reliability, and that he was finally showing some independence, Craig didn’t hesitate saying yes. But as one hour bled into three – the dog had emerged from the basement, a sign the fireworks were over – our studied ease morphed into full-blown panic. Craig went out on his bike to look for Finn, his orbits of the dark, nearly abandoned park quickly growing to encompass neighbouring playgrounds and schools; all were empty. Finn was underdressed in a dark T-shirt and shorts; he’d left his cell phone and wallet at home.

We were on the phone describing him to the police, just past midnight, when he burst through the door, called out a typically cheerful Hello. His cheeks had a deep flush. He was parched. When we told him of our fear and worry, his reaction was incredulity. He’d taken Craig’s words – something along the lines of, “Come home when you’re done” – the way he takes everything, literally, and so when he made the spontaneous decision to walk downtown to see the skyscrapers lit up at night it hadn’t occurred to him to tell us. Along the way he’d stopped off at Toronto City Hall to ride the elevators in the underground parking lot for a bit. Round trip, the journey was six kilometres.

***

Now sixteen and over six feet tall, Finn is slim and handsome. He has curly brown hair and blue eyes that are as round and unguarded as they were when he was a baby. Sports hold little appeal for him, but he’s a champion walker who, despite a gait that’s somewhere between Charlie Chaplin and a forward moonwalk, seems propelled by an unseen force. An occasional runner, I can’t keep up with him unless I jog. He loves to talk, and will do so incessantly if the topic compels him.

Because it taught him to walk and talk, pinball is partly to blame for Finn’s Victoria Day escapade. Not that he couldn’t do these things before – he wasn’t, like the eponymous hero of the pinball-themed musical Tommy (whose name, oddly enough, is Tommy Walker), mute, though autistic kids can be – but partly due to his disability, partly to what seemed like innate sedentariness, he took a minimalist approach to them. Walking further than a couple of blocks, pre-pinball, involved pushing, dragging, or carrying him. “Conversations” were one-way, circular affairs aimed at the surgical extraction of information, or at getting reassurance for something that might or might not happen. At thirteen, Finn’s inactivity was a concern; I was conscious of him crossing the line into “Husky”-sized jeans. So when he showed signs of what would turn into a years-long passion for pinball right around the time a hipster arcade called the Pinball Café opened in nearby Parkdale, in January 2012, we made Finn an offer: he could play several times a week, including evenings after school, as long as he walked there and back – six kilometres in all.

But an addict will say whatever he needs to get his next fix. So although Finn’s eyes were bright when he agreed to our terms, the pleading to hop on transit, to take a cab, often started after just one or two blocks. But we remained stalwart. Craig, who accompanied him most often, became adept at a perambulatory sleight-of-hand: placating Finn with promises to take the next streetcar – just keep walking – he timed things so they were always between stops when it went rattling by. He initiated games of chase that had them deking around leafless trees and ambling pedestrians. As they ran, laughing, down Queen St (Finn’s laugh, which in its highest form involves a soundless, teary-eyed shaking that causes his knees to buckle, is one of his legion charms), their chemistry had an uplifting effect on passers-by, most no doubt unused to seeing a teenage boy act in such an effervescent way with his dad.

***

Pinball’s spinning balls, twirling gates, electronic and mechanical sounds, vivid colours, blinking lights, “themes,” rails and ramps, music, numbers, countdowns, rules, and physics in action are, for those on the spectrum (as autism is often referred to), akin to a sensory gingerbread house. Finn, whose childhood love of marble mazes and spinning anything had already transferred, in his tween years, to Rube Goldberg machines, Foucault’s pendulums, kinetic sculptures, domino runs, pipe screensavers, and model railways – the constant being a certain kind of motion, usually funnelled, that puts other elements in play – was always going to succumb to pinball’s charms, it was just a question of when. (A Canadian pinball historian once referred to the game as “sculptures you can play.”) I took him, for years, to the massive George Rhoads rolling-ball sculpture at the Toronto Science Centre, knowing I could read the weekend newspapers cover to cover while he soaked up its various facets.

Testing for autism sometimes involves giving kids a toy train or car to see if they play with it “appropriately.” Most autistic kids will pick it up and spin the wheels at eye level. Finn did this during his own 2003 assessment, when he was four. The Montessori school in which we’d enrolled him, despite the outlandish cost, in the hopes that what we took to be his “eccentricities” would be embraced, had called to complain he was eating the entire class’ snack supply, that he wouldn’t leave the music room. Though early on we’d ruled out autism because Finn’s affectionate nature didn’t figure in the descriptions we found online, we knew a positive diagnosis was a strong possibility. Still, it was only when he ignored the testers’ entreaties to sing “Happy Birthday” to a plastic doll so he could hold a CD up to the light to see the rainbow reflected on its surface that we knew it was a done deal.

Finn’s autism isn’t Asperger’s (Bill Gates, et al.); nor is he a glamorous, party-trick savant who can, like Daniel Tammet, recite pi to 22,514 digits, or know, at a glance, like Kim Peek (aka Rain Man), how many matchsticks are in a pile (I once tried this, just to see, and he got down and started counting them; I told him to stop). Finn has regular, garden-variety autism. He loves math, especially geometry, but isn’t a prodigy; can decode words and texts at age level, but comprehends them well below this. He has an uncanny sense of direction and photographic memory for detail, which means I rarely need a GPS when I drive with him. Because he’s verbal, some would call him “high functioning,” though as Steve Silberman, author of the neurodiversity-positive book NeuroTribes (2015), has pointed out, terms like high- or low-functioning can obscure as much as they reveal: high-functioning people often struggle profoundly with invisible, day-to-day aspects of their lives, while low-functioning people may simply lack the appropriate methods of communication.

Like many people on the spectrum, Finn’s life is ruled by a number of deep interests. You could call these “obsessions,” though the term, in autism circles, has become somewhat verboten: people tend to use it disparagingly when they don’t “get” someone’s enthusiasms. (Collecting hockey cards is a passion, while memorizing license plates is an obsession.) Some of these change: lighthouses, water towers, Toy Story characters, and tigers have faded, while others, like subway systems, hotels, and construction cranes have proved enduring. Colour, numbers, and music move him in the way religion moves others (the first time he saw a crucifix he asked me why they’d put a man on a plus sign). He’d grasped, by the age of three, the fundamentals of colour theory; has always been happy to spend hours a day listening to music (which seems perfectly normal now that he’s a teenager.) Of course, to some degree this is true of everyone. Once you learn about the spectrum it’s impossible not to see it all around you, or to place yourself on it in some way, so you could backward-engineer things and say that autistic people are rarely jack-of-all-trades generalists.

His career goal, forever, has been to be a crane operator. This isn’t entirely unrealistic in a city that’s in the midst of a construction boom like Toronto. The problem is that construction doesn’t really interest him per se; his appreciation of cranes hews more along aesthetic lines. He loves their taxonomy: height, colour, types, and design. The cut of their jib, so to speak. Contrary to what many people assume, these obsessions (I’m going to reclaim the term here for a second) make him a deeply gratifying kid to parent; the joy-payback is high if you give him access to what he loves. Presenting him with something of limited or no interest, on the other hand, has a soporific effect, renders him sluggish, noodle-like.

Though Finn needs many things broken down and explained to understand them, like social rules, he absorbed pinball’s often insanely complex gameplay effortlessly, in a kind of gestalt (this varies for each machine, but usually requires accomplishing a series of tasks in sequence when prompted by the display or playfield). He can read the feedback on a display and focus on the playfield at the same time, which means no detail, aesthetic or mechanical, escapes his attention. On a recent trip to an ear-bleedingly loud suburban arcade, he abruptly quit playing “Star Trek: The Next Generation,” disgusted that a tiny drop gate wasn’t working. When the technician we summoned assured Finn that the needed part had been ordered, he perked up again. Things not working the way they should causes him tangible grief.

***

Pinball’s eighty-year history is, like the game itself, full of highs, lows, interruptions, sudden turns. For its most devoted adherents, the game’s shift, in the fifties and sixties, from electromechanical to solid state – which replaced the satisfying thunk of rolling scores and relays with bleeping microprocessors and circuit boards – was as shocking as Dylan going electric at Newport.

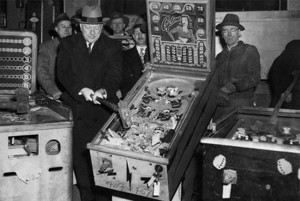

pinball and syphilis combined.” And indeed pinball had, for a time, something of an outlaw image, largely due to a long period of prohibition. For thirty years, from the mid-forties through to the mid-seventies, it was banned from most major American and Canadian cities (Montreal still doesn’t allow it in bars). This included its spiritual home, Chicago, where all the major companies (Bally, Gottlieb, Williams, Stern) were once headquartered. The ban came about in the pre-flipper era – Gottlieb’s 1947 “Humpty Dumpty” machine was the first to use electromechanical ones – officials arguing that pinball was a game of chance and therefore promoted gambling. (This wasn’t without justification given that some machines had payouts.) After the ban,

pinball machines were burned in pyres, a spectacle evoking, among other things, the Nazi book burnings of the previous decade. New York’s Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia, who’d initiated the ban, was photographed sledgehammering machines that were later dumped into the city’s rivers like the bodies of mob hits. Any self-respecting pinballer still routes his flights through JFK.

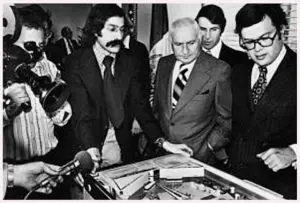

The ban continued until 1976, when the American game lobby conscripted pinball’s best player, a young, prodigiously mustachioed journalist named Roger Sharpe, to prove to officials that pinball was a game of skill. After Sharpe managed, in a packed Manhattan courtroom, to call and land a shot straight up the playfield on a machine he’d never played (suspicious of a fix, they’d asked him to use the back-up machine that had been brought in case the primary one conked out), the council members in attendance re-legalized it on the spot. Sharpe has been considered the game’s Babe Ruth ever since.

The ban continued until 1976, when the American game lobby conscripted pinball’s best player, a young, prodigiously mustachioed journalist named Roger Sharpe, to prove to officials that pinball was a game of skill. After Sharpe managed, in a packed Manhattan courtroom, to call and land a shot straight up the playfield on a machine he’d never played (suspicious of a fix, they’d asked him to use the back-up machine that had been brought in case the primary one conked out), the council members in attendance re-legalized it on the spot. Sharpe has been considered the game’s Babe Ruth ever since.

***

When, after two months of three or four weekly walks to Parkdale, Finn finally found his pinball legs, the transformation in him was astonishing. Despite a compensatory diet of shrimp lo mein, pizza, and black-cherry sodas, he shed weight. More significantly, the salubriousness of the walk, full as it was with the anticipation of something deeply desired, made him brightly talkative. When he was four or five and what little speech he had was often echolalic (the parroting back of phrases, verbatim), meltdowns were a regular part of our everyday life. The doctors and therapists we consulted had told us this behaviour would diminish as his communication skills increased, and this proved to be true. Finn’s pinball career, and the walks that enabled it, coincided with the waning of his hairy fits.

As Finn’s verbal abilities improved, the urban landscape between us and the Pinball Café – which remains, despite over a decade of gentrification, a transitional place where soup kitchens abut trendy taquerias, a psychiatric complex, Tibetan restaurants, and Indian groceries – elicited a new kind of curiosity, one that, for the first time, produced follow-up questions. Encountering people who spoke to themselves made him conscious of his own self-talking habit; that many were psychiatric patients, or homeless, or both, contributed to an incipient social awareness.

Owner Jason Hazzard traded up the Pinball Café’s seven or so machines fairly often, which gave the visits there an advent-calendar-like thrill. (Kids with autism have the reputation of disliking change, but this has never been true of Finn.) Our arrival had a ritualistic quality. After throwing open the door, saloon-style, Finn would stride purposefully towards the machines, say a quick Hi to Jason or his wife, then deliver, in full outdoor voice, a pinball state-of-the-union. Finn had never been one to chat with strangers, but now, while waiting for games, he offered tips to other players that turned into proto-conversations. As patrons began to recognize and greet him, asked if he wanted their unplayed credits, he found out, and embraced, what it was to be a regular in a place. On each visit he was given about five dollars to play with; when that ran out it was time to go home. So he got better, fast, and figured out how to economize: three plays for a dollar is better than one for fifty cents. When he arrived home a couple of hours later, flushed and rosy-cheeked like a Victorian child still grasping his stick and hoop, he gave a full rundown of that evening’s entertainment; wrote in the log he started to keep, and still maintains, of all the games he’d ever played.

***

The top-ranked pinball player in Canada, and the fifth ranked in the world, is a twenty-seven-year-old autistic man from Vancouver, Robert Gagno. Gagno, who’s the subject of an upcoming documentary, Wizard Mode, reminds me a lot of Finn in both looks and manner. Tall and lean with wavy brown hair, he has an endearing ingenuousness and a sweet smile. One of Gagno’s special abilities is that he can track a pinball without moving his eyes. He can do this even in multiball mode, which makes most people unattractively cross-eyed. Though his parents were told when he was little that he might never talk or walk (he was non-verbal till age seven), Gagno now speaks articulately and passionately about his chosen sport, owns his role as a torchbearer for the autism community.

Gagno appears to blend seamlessly into the pinball world, a milieu where Finn, too, can “pass” for neurotypical (as people not on the spectrum are called). His love for pinball naturally enhances Finn’s sociability, his desire to communicate and comment. That it doesn’t require eye contact is a bonus, though this has improved as well. Finn and Gagno share a low-key, unostentatious pinball-playing style that contributes to their outward-seeming neurotypicalness. This is even more interesting given that good neurotypical players sometimes exhibit behaviour that could be taken for autistic, a phenomenon Gagno himself has remarked on:

Other pinball players, especially in tournaments, do things that might seem odd if they did it in a public place like a mall or grocery store. Some players talk to themselves or to the pinball machine and say random things, they jump up and down or pace, some wear headphones, and they are just as obsessed with pinball as I am.Outside of the pinball tournament that would look autistic! It’s okay if I don’t feel like talking or if I just want to play on my own. Pinball might be one of the only sports where it is okay to turn your back on people and it is even expected. Sometimes it is still confusing figuring out people’s behaviours but less confusing than, say, at a birthday party.

Now one of pinball’s respected elder statesmen, Roger Sharpe illustrates the point. Though Sharpe’s speaking manner is calm and measured (he refers casually to “becoming one with the machine”), his business-on-the-top, party-on-the-bottom playing style is what you might call a vertical mullet. Anchored by his hands on the flipper buttons, Sharpe’s upper body stays relatively still while his lower half moves restlessly, like a slo-mo Irish dancer. In a signature move, one foot comes to rest momentarily on a bent standing knee, as in a modified tree pose, before it swings around and whip-kicks behind him. Multiple World Pinball Champion Rick Stetta is even more flamboyant: he can collapse down fully on both knees; sweep the air with his hands, after flippering, like a mime; bring his knee right on top of the playfield. (Both men can be seen in action in the excellent 2009 documentary, Special When Lit.)

***

That some pinballers might have undiagnosed autism is certainly possible. The first time we went to Pinball Faith Night, a monthly event run for eighteen years by Michael Hanley at his labyrinthine private space in Mississauga called the Church of the Silver Ball, Hanley’s wife, Christine, greeted us at the door. When she saw Finn, she grabbed him by the shoulders and kneeled to his eye level before slowly and deliberately explaining the Church’s rules. As this was the way therapists had always spoken to Finn, we assumed she knew he was autistic, but when we asked her about it she just shrugged: that was how she spoke to all of the Church’s pinball guests.

On Pinball Faith Night no quarters or loonies are required. For a flat admission fee you can play unlimited pinball on about thirty unlocked games, which range from classic electromechanical – their backglasses tending to feature happy white people doing wholesome activities like bandleading or surfing – to more recent, solid-state ones. Dozens of others in various states of functionality are stacked, ceiling-high, in the warehouse’s wooden rafters. Hanley is on hand the entire evening, happy to talk about any aspect of pinball, of which he has an encyclopedic knowledge.

Part of the Church’s allure is that it has both Pinball 2000 games, “Attack From Mars,” and “Star Wars: Episode 1,” which, aside from being massively fun, also represent a pinball watershed. Faced with plummeting sales in the late nineties due to stiff competition from home-console video games, the industry’s dominant player, Williams, had given its best minds the unenviable task of inventing something to save pinball. (Though it’s tied in our cultural imagination to the seventies, pinball peaked economically in the early nineties with the advent of its bestselling game, Bally’s “Addams Family.” Its fortunes went into rapid decline immediately afterward.) The result, in 1999, was Pinball 2000, a video game-pinball hybrid in which you shoot at holographic characters projected on the playfield. The games were great, and sold well, but when Williams realized it was essentially in competition with itself, it abruptly shuttered its pinball division to concentrate on more profitable slot machines. Pinball, which in its heyday had dozens of manufacturers, now had only one: Stern. (A story told in the interesting but bizarrely soundtracked documentary Tilt: The Battle to Save Pinball.)

***

There’s something synaptic about pinball. Watching Finn play, it’s easy to imagine the playfield as a metaphor for his thought processes, from the ball’s launch via the plunger to its fluid, frictionless trajectory through gates, over ramps, off slingshots and bumpers, its lighting up of neural-ish pathways before eventually draining through the flippers or outlanes. When Finn’s behaviour becomes “sticky,” when he gets caught in an idea-loop that compels him to ask the same question over and over, it feels like a ball looks when it ricochets between triangulated thumper bumpers; the temporary insanity of multiball. We’ve learned the hard way that patience is essential in these instances. Get pushy or aggressive with Finn and he tilts into a meltdown, ending any advantage you might have had.

Tempting as it is to compare Robert Gagno, or Finn, to the character Tommy, who uses pinball to overcome the PTSD-like condition he suffers from as a result of having seen his mother’s lover killed by his father – “Ain’t got no distractions/Can’t hear no buzzers and bells/Don’t see no lights a-flashin’/Plays by sense of smell” – in reality it’s the opposite: Finn hears, sees and, for all we know, smells all the lights, buzzers, and bells. But for him they’re not distractions, they’re an integral part of the experience. Robert Gagno has said, similarly, “I like the music, the lights . . . everything. You can almost combine it all together, kind of thing.”

To psyche himself up for competition, Gagno listens on headphones to three artists on rotation: Bryan Adams, the Black-Eyed Peas, and Anne Murray. There is, as of yet, no Anne Murray pinball game, though many machines are themed on musical artists. That said, genre-wise options are limited. There are, for example, several Metallica games (among them “Metallica: Premium Monsters,” and “Metallica: Master of Puppets”), three Kiss games (Limited Edition, Premium, and Pro) as well as Rolling Stones, AC/DC, Guns N’ Roses, Ted Nugent, and The Who games. (Astonishingly, no Rush game exists, though hobbyists have produced customized ones.) Dolly Parton is one of the few female musical artists to have a game, but if you’ve spent some time around pinball you’ll know this wasn’t an attempt to win over women, or Grand ‘Ol Opry fans.

In fact, only one woman, Helena Walters, currently ranks in pinball’s top hundred (in 2015, she was sixty-sixth). And while there are likely many reasons for this, one strikes me as obvious: a pinball game whose artwork doesn’t feature a woman is rare, one that doesn’t portray women in the most overtly sexist way possible rarer still.

Pinball’s take on women is like its take on music, predictable and monolithic. In pinball artwork, women are almost uniformly giant-breasted, tiny-waisted, white, and wrapped like twine around the leg of whatever male hero they’re there to adorn (a 2009 California gallery retrospective of the pinball artist Dave Christensen was called “Broads, Boobs and Buckles: The Pinball Art of Dave Christensen”). The 2002 Playboy game featured interchangeable clothed and nude photo inserts, though the promotional flyer was arguably more suggestive than the game itself (“Execute the skill shot to open this toy”; “Centrefold toy unfolds at the start of three-ball multiball.”) In some ways, the static imagery of a pinball backglass exacerbates this problem. Though video games get all the flack, some, like Final Fantasy, Resident Evil, or Tomb Raider at least offer the possibility of playing as a female character, even if it is in skimpy clothes and heels.

The potent sexual allure of the pinball wizard became, in the seventies, part of the game’s mythology. The pinball-obsessed protagonist in Haruki Murakami’s early novel, Pinball, 1973 is so good at his favourite machine, Spaceship, that “high school girls in bright red lipstick would rub their soft breasts against my arm as I pressed the buttons.” After the arcade where he plays disappears, he ends up in a warehouse full of salvaged machines, where he is greeted with the following sight:

the women . . . Blondes, platinum blondes, brunettes, redheads, Mexican girls with raven hair, ponytailed girls, Hawaiian girls with hair to their waists, Ann-Margret, Audrey Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe . . . each thrusting out her glorious breasts from beneath diaphanous blouses unbuttoned to the waist, or one-piece bathing suits, or pointy bras . . . Their colors would fade, but their breasts would retain their eternal beauty. The lights flashed on and off as if in time with the beating of my heart. The seventy-eight pinball machines were a graveyard of old dreams, old beyond recall. I walked slowly past those dream women.

Later, when the relationship between Murakami’s hero and his beloved game starts to take on a sexual dimension, he gets to play the wizard in more ways than one: “ . . . she was marvelous. The three-flipper Spaceship . . . only I understood her, and only she truly understood me. Each time I pressed Play, she sang that gratifying melody, flipped her board to six zeroes, and smiled at me. I coolly pulled the plunger back to the perfect spot, not a millimeter off, and launched the gleaming silver ball up the chute and out into her playfield. Watching it bounce around, I felt as free as if I had smoked a pipe of the finest hashish.”

One of Finn’s favourite machines at the Pinball Café, the 1980 female-robot-themed “Xenon” – the first game to “speak” directly to its player – is an exception that proves pinball’s sexist rule. Despite being, according to Marco Rossignoli, in his definitive The Complete Pinball Book (now in its third edition), “one of the sexiest pinballs ever built,” only Xenon’s face appears on the backglass, her giant, bulbous eyes acting as visual placeholders for absent breasts (of which there are a few on the playfield, but hell, it’s a start). Unusually, Xenon was voiced, and the game’s music written, by a woman, the electronic-music composer Suzanne Ciani, who went on to receive several Grammy nominations for her New Age albums in the eighties and nineties. Xenon may be a robot, but she still has feelings. Each time Finn flicks a shot off her bumpers, she responds with a low, pleasurable moan (Ciani’s, presumably). Finn’s attraction to Xenon perhaps isn’t surprising given that for a long time he considered Leela, the well-endowed Cyclops character from Futurama, to be the pinnacle of womanhood.

Another female-robot game, “Bride of Pin Bot,” created a minor controversy in 1993 when it was removed from the Harvard campus following multiple complaints of sexism by students and staff. “Bride of Pin Bot” is one of a few pinball games that attempts a kind of narrative structure. Your goal is to “awaken” the bot, then turn her into a human. This is done in four stages on a playfield that looks a bit like the old game of Operation (if the guy being operated on had sported giant red nipples, that is). Shooting balls into the Bride’s open mouth reveals a second face, its mouth closed but eye sockets empty for loading balls into. Bringing about the full metamorphosis involves a two-ball multiball. On her playfield, the Bride has wider hips than one would expect a robot to have and “Danger, High Voltage” is written above the equivalent of her pubic bone. Between her legs, a rocket with its thrusters on full and a tiny, flag-wielding American astronaut astride its nose is about to penetrate her. “Make me feel like a woman,” she pleads via the game’s fourteen-segment alpha-numeric display.

In the Harvard Crimson’s report on the incident, representatives from the game’s distributor, Woburn Vending, did their best impressions of chauvinists from central casting:

“Doesn’t anyone have a sense of humor there?” [employee Doug Spitnaly]asked.

Charlie Vessey, also with Woburn Vending, said these are the first complaints the game has received, even though it was located for months in the basement game room of the Harvard Freshman Union. However, he said he could understand why some people might be offended. “After I saw it, I could understand a little,” he said, “Not that I agreed.”

***

After half a decade watching Finn play pinball, I’ve come to see the game’s priapic, adolescent-fantasy aspect as more tiresome than offensive. It’s too easy to imagine the original sketches for pinball’s awkwardly rendered bimbos, rocket ships, centaurs, and tough guys drawn in leaky blue ballpoint pen on lined paper by a pimply fifteen-year-old boy killing time in math class. And pinball’s sexism doesn’t really come close to the sexism and misogyny of the video-game world. Pinball has, as of yet, no equivalent of Gamergate. Google “sexist pinball” and the first hit you get is a link to “The Top Ten Sexiest Pinball Backglasses Ever,” suggesting either that a feminist critique of the game is overdue, or that there really is a fine line between sexist and sexy, as Spinal Tap’s Nigel Tufnel had it. (Googling “sexist video games” produces, in contrast, the predictable tsunami of results.)

Many of pinball’s cataloguers and historians, who are – no surprise – almost exclusively male, seem oblivious to pinball’s political incorrectness. In Heribert Eiden and Jürgen Lukas’ Pinball Machines (1997), the caption to the artwork of a 1974 Mexican-themed Bally game called “Amigo,” in which a barefoot, gap-toothed, sombrero-wearing, Disney-eyed Mexican peasant rides, guitar in hand, backwards on a donkey, notes that “the illustration borders on caricature.” This made me wonder if I actually knew what a caricature was; is the Mexican man’s head too in-proportion to the rest of his body to qualify? In their description of Bally’s Australia-themed “Boomerang,” on the other hand, Eiden and Lukas become effusive, noting the backglass’ “sensitive and accurate details,” which include an “older aborigine looking skeptically at you” (this is true). And yet while they note, again correctly, that Ayer’s rock is actually red and not, as the artist had it, yellow, they are conspicuously reticent when it comes to the verisimilitude of, say, the physical proportions of pinball’s women, choosing instead, to focus on more positive things (“The showgirls are doing the French CanCan, which requires fast action and high kicking.”)

Stern’s basketball-themed “NBA” is another of Finn’s favourite machines at the Pinball Café. As I watch him shoot the pinball through the game’s miniature hoop, however, what strikes me most about it is the African-Americans on its backglass; the Harlem Globetrotters aside, black people are almost non-existent in pinball art (Native Americans, in contrast, appear far more frequently). One of the few exceptions, Playmatic’s “Black Fever” (1980), features three black women in requisite bikinis and high heels holding weirdly elongated guitars. (one assumes they’re in a band). The first has a planet-sized afro, the other two gushing fountains of Tina Turner-style hair. But none appears to have any kind of fever, scarlet or otherwise. (As always, its hard not to read the game’s publicity sheet as sexually suggestive: “FEATURES: Outside button to allow the player to play balls alternately or continuously.”) So what, you might ask, does Marco Rossignoli have to say about this gender/race whammy? Merely that “Black Fever” was one of the few machines to feature offset flippers (one flipper was about an inch further up the playfield from the other), which, when you think about it, is pretty special.

***

Thanks to autism’s ubiquity, there are now countless options for therapy. We did music therapy for a while, which was fine, but what you eventually learn is that “therapy” is anything that produces positive change, and that the most effective forms of it tap into what naturally motivates and interests a child. Kristine Barnett describes an extreme version of this in her 2013 book, The Spark. Barnett had been told that her severely autistic son, Jake, might never walk and talk. So she was surprised to discover, when she took him, at age three, to an astronomy lecture at the local observatory, not only that he could string together a perfect sentence, but that he possessed a graduate-level understanding of lunar gravity. By age twelve, Jake was a graduate-level quantum-physics researcher with a published paper on lattice theory. Saddled with a similar prognosis in his early years, Robert Gagno has been part of the inspiration for Pinball Edu, an American non-profit that harnesses pinball for the social enrichment of those both on and off the spectrum.

The Pinball Café was Finn’s therapy for eight months. After that it was closed for, among other things, failing to comply with the City’s pinball-prohibition-era bylaw mandating that restaurants have no more than two “pinball or other mechanical or electronic game machines” on their premises. Before its doors shut for good, we bought Finn’s favourite machine, Bally’s 1979 “Mystic,” which now sits in the lobby of the post-production studio Craig runs. This has fostered other skills: when one of “Mystic”’s solenoids blows, Finn orders the part, then replaces it himself.

Though the bait has changed – it’s now skyscrapers, elevators, cranes – Finn and Craig still go out for long walks, usually on weekends. These require no cajoling. In November we took a three-day trip to New York City and spent a good portion of it riding elevators for fun, and it really was. As for pinball, Finn now has sufficient social and money skills to play on his own at the handful of places within walking distance of our house: an Italian sandwich joint, a tavern, a Vietnamese karaoke bar.

Last Friday night we drove to an industrial park near Pearson Airport. The Church of the Silver Ball was reopening after a three-year hiatus. Finn talked effusively to Michael Hanley, who couldn’t believe how tall he’d gotten, and played some of the games he’d missed: “Cirqus Voltaire,” “Tales of the Arabian Nights,” “The Who’s Tommy.” Reid parked a stool in front of Pinball 2000’s “Star Wars: Episode 1” and stayed there for most of the night. I played an old Bally game with artwork by my favourite pinball artist, Jerry R. Kelley. If pinball, whose art too often falls between kitsch and lousy, has a Picasso then I figure it is Kelley, whose Cubist-inspired graphics, with their modish pea-green and dusty-pink palette, appeared on a number of games from 1966–1971. His greatest, “Capersville” (1966), which was inspired by Godard’s Alphaville and is the only pinball game I know with direct ties to the French New Wave, features the film’s American actor-singer star Eddie Constantine on its backglass. Kelley’s attempts to bring a whiff of high art and intellectual sophistication to pinball appear to have been mostly unsuccessful, however. These days, “Capersville” is appreciated mostly for its pioneering three-ball multiball. It was also the second game to have “zipper flippers,” which closed up to prevent the ball from draining when certain goals were achieved.

***

Pinball seems unlikely to re-attain its Addams-Family high of the early nineties, so it surprised many when, in 2013, a new manufacturer, Jersey Jack Pinball, came on the scene to give Stern its first competition since the 1999 demise of Williams. Jersey Jack founder Jack Guarnieri, an industry veteran who got his start servicing electromechanical machines in the seventies, has taken a high-end approach to the venture, his aim being to marry the best artists with the newest technology. The company’s only game to date, “The Wizard of Oz,” includes, among a long list of bells and whistles, digital stereo sound, an LCD-monitor backbox, and a crystal ball in which Margaret Hamilton’s Bad Witch appears. Technologically, it’s a shift arguably as significant as the mechanical-to-electronic one, though as the Pinball 2000 debacle showed, technology alone can’t save pinball. (Michael Hanley told me he finds the game aesthetically pleasing, but the gameplay a tad disappointing.) Guarnieri says he licensed the “Wizard of Oz” to tie into the film’s seventy-fifth anniversary, but also because he believed it would cast the widest possible net demographically.

From CNQ 95, The Games Issue (Spring 2016)

1 Comment

Pingback: Pinball: A Walking Tour by Emily Donaldson – CNQ | Fun With Bonus