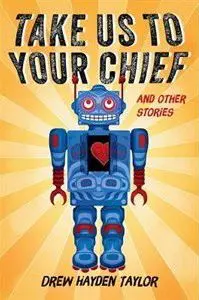

Genre has never been an impediment for writer, journalist, humourist, and playwright Drew Hayden Taylor, the “blue-eyed Ojibway” whose almost 30 books include novels (one of them a First Nations vampire story for teens), drama, non-fiction, and a series of collections on the Native experience—Me Funny, Me Sexy, Me Artsy—which he edited and contributed to. His latest, Take Us to Your Chief (Douglas & McIntyre), a short-story collection, is being promoted as “classic science-fiction stories reinvented with a contemporary First Nations outlook.”

Brad deRoo: What did you learn writing sci-fi?

Drew Hayden Taylor: I don’t know that I learned anything via sci-fi, any more than I learned from other genres. The thing about sci-fi is that its function and purpose is the same as any other genre, to explore the human or social experience. The only difference is they use different tools. Sci-fi, in general, was partially created as a method of exploring issues and concepts that the general audience might not be interested in as, say, an essay. Instead, if presented in sci-fi, you have a good story with a message and point cleverly hidden by the exoticism of machines, aliens or what ever. At its core, sci-fi functioned as good metaphor. Look at Frankenstein, 1984, Brave New World, The Time Machine etc. All have a larger resonance than just what lies on the page.

BdR: I think one of the finest traits of sci-fi is its ability to quickly make the mundane fantastic, to make the everyday uncanny. Was this immediately appealing to you? Was it ever difficult to embed the fantastical in the real?

DHT: The fact that science fiction doesn’t necessarily have to do with spectacular technology or aliens really did appeal to me. Only a few of my stories dealt with any substantial hardware. For me the appeal is always the same with any type of writing — exploring the human experience, just using different tools. It’s like cooking a stew, sci-fi is just using different spices/ingredients to make your stew. All the stories in this collection have the human element at their core.

Imagining the fantastic was never the difficulty. Frequently, not imagining the fantastic was occasionally the problem. I’ve written a vampire novel, a magic realism novel where the Trickster appears with interesting abilities etc. Sometimes we Native people have too much reality, and this was my way of dealing with it.

BdR; Are there other genres ripe for reinterpretation in the manner you have chosen here?

DHT: Horror might be next. I have heard rumours that several Native authors are working on a Wendigo novel. I have had an idea on how to tackle it myself but now, with so much interest in the story, I don’t know if I just want to be ‘one of the crowd.’

BdR: “Contact” is a critically referential point in these stories. What about contact – in the context of sci-fi – worked fictionally for you?

DHT: Contact was an obvious topic to be explored in a book of Native science fiction. The image of those ships coming over the horizon all those years ago could not have been any more startling than having a flying saucer land in the backyard. In fact, I believe I have contact with aliens in two of the stories, one with a sad ending, one with a humorous, positive ending. I think it’s obvious why it worked for me as an aboriginal writer… two completely different cultures meeting and interacting. Seemed like a natural. Writing those stories gave me the opportunity to come at contact from several different perspectives and play with what could happen.

Contact could become a dominant metaphor in writing Native sci-fi because of that collective experience. I created the term Post-Contact Stress Disorder to explain the myriad of social issues many First Nation communities are still dealing with, centuries after that first and subsequent contact.

BdR: Why do you think we’re so fascinated by aliens? Do you ever find yourself delving into reports of sightings?

DHT: When I was younger I used to read all those books about abductions and sightings etc. They were fun and escapist. Nowadays, I am more interested in actual astronomy and science. Whether they are legitimate or not is a difficult question. It’s a huge universe out there, so on one hand it’s virtually impossible to categorically say there is no other life possible in the vastness of creation. But again, it’s a big vast universe with immense distances and unbreakable laws of physics, how they got here and where they came from is an even more daunting question.

by Drew Hayden Taylor

Douglas McIntyre, 160 pages

BdR: Many of these stories are rooted in satire. What about satire elucidates?

DHT: I love satire. Much like metaphor, it’s an opportunity to say one thing while actually saying another. It’s like camouflage. It’s like writing two stories at once, with one making you smile and think at the same time. I am a big fan of satire and I think it can open certain intellectual doors straight stories can’t. It’s also lots and lots of fun. And a book like this should be fun.

BdR: Satire can be very good for talking about very serious things in humorous ways. Many of your stories here certainly do that. Do you find humour to be healing?

DHT: I write a lot of humour and on occasion I have had my wrist slapped by some for celebrating the more positive and delightful part of our culture, and not focusing on the more dysfunctional aspect of our existence. A large part of my decision came from a conversation I had with an Elder in Alberta who told me that in his opinion, for Native people, “Humour is the WD40 of healing.” That stayed with me and I can really understand and appreciate that. I think it was an American Native writer who once said something to the effect of “the best way to understand a people is through what makes them laugh.”

BdR: Your stories also speak truth to power. What’s the place of story in truth and reconciliation?

DHT: That’s a head-scratcher. For me the difference is that journalism is telling the truth about lies while fiction is telling lies about the truth. As for truth and reconciliation, I think it was Tom King who said, and you have to find the correct and accurate quote, “For us, stories are all we are.”

BdR: Is there anything else you’d care to discuss? Anything you hoped I’d ask about but didn’t?

DHT: I think you might want to mention something about how exciting it is for Native writers today, with all the exploration of genres hopping out there. We’re constantly exploring the boundaries of what’s possible, and different ways of exploring the Aboriginal perspective. For instance, Kateri Akewenzie-Damm published a collection of Indigenous erotica from cultures around the world. Daniel Heath Justice wrote a trilogy containing elves, swords, sorcery, and monsters, Tom King’s not-so-secret hobby is writing crime fiction. These are exciting times. Who knows what’s next… 50 Shades of Red?

—A CNQ Web Exclusive, October 2016