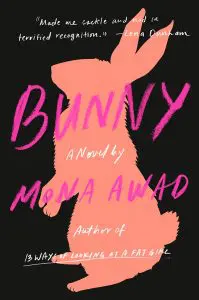

by Mona Awad

Hamish Hamilton, 320 pages

Samantha Heather Mackey isn’t like the other MFA students at Warren University, an Ivy-League school in a seemingly quaint New England town. She doesn’t vacation in the Hamptons, squeal with delight at the sight of her cohort, or outfit herself in tulle and pastels. The protagonist of Mona Awad’s new novel, Bunny, is a creative-writing student on a scholarship who barely gets by on stipend cheques. She’s no stranger to darkness—family issues lurk in her past—but even so, she’s unprepared for the violent events that follow after she accepts an invitation to attend a “Smut Salon” hosted by the clique of rich girls (or “Bunnies”) she so loathes.

Samantha doesn’t particularly want to spend time with these women, whom she nicknames Duchess, Cupcake, Creepy Doll, and Vignette. They have an eerie way of moving, speaking, dressing, and eating in exactly the same manner. But she worries that turning down this gesture from the only other participants in her small, all-female workshop will result in a hostile classroom atmosphere. It doesn’t help that attending the Smut Salon will seem like a betrayal of Samantha’s only real friend: the black-lace-clad, sarcastic, self-assured Ava. When Samantha shows up, she’s subjected to a bizarre reading of Michael Ondaatje’s “The Cinnamon Peeler,” which Cupcake (whose real name is Caroline) recites as she shaves pieces from a cinnamon stick with “increasingly fast, fevered strokes.” The Bunnies are then expected to offer feedback: “I love the way the erotic is rendered as a tactile, olfactory experience,” says one. Afterwards, “they all sigh collectively, as if post-orgasm.”

The most impactful part of this scene—and the entire novel—is the portrayal of the Bunnies as self-serious caricatures of privileged, indulgent, narrow-minded white girlhood, and the unmistakable fun Awad clearly has in writing them. But the joke turns out to have a sinister, supernatural punchline. As Samantha begins to participate in the Bunnies’ out-of-school workshops she becomes increasingly isolated from her genuine friendship with Ava. It’s when Samantha’s voice dissolves from an “I” into a polyphonic, Bunnified “we” that we realize her mind is melding into theirs: “We love you, Bunny.” The workshops turn out to be sessions in which the girls transform rabbits into “Drafts”: empty-eyed, mutilated human males that the Bunnies use for entertainment when they’re “borny” (bored and horny). The Drafts speak adoringly to the Bunnies, using phrases the latter plant in their minds. They run the Bunnies’ errands, and occasionally die by axe-blow when a Bunny feels the need to “kill her darlings”—if they don’t explode first, that is.

Anyone who’s endured a creative-writing workshop will find Awad’s satire of academic language—its vagueness and pseudo-intellectual references to feminist theory—particularly searing. The Duchess engraves her “proems” into panes of shining glass, while Vignette writes vignettes about “a woman named Z who pukes up soup while thinking nihilistic thoughts.” “It’s just always so interesting how you engage the Body,” a Bunny says, “so interesting how she performs and re-enacts trauma.” Meanwhile, Samantha’s work is met with wrinkled noses. It’s “angry,” “abrasive,” and “just way too invested in its own outsiderness,” especially when she manages to get some distance from the Bunnies. Even more maddeningly, their professor, Ursula, seems to be a grown-up version of the Bunnies, blind to how superficial her own words are: “These sorts of difficult conversations…. How they open us up. The Wound is tapped and it bleeds.”

Awad builds a nightmare MFA out of components she seems to know intimately: a sharp loneliness, a town so picturesque the light appears stilted, a literary program that churns out dozens of successful experimental writers. There’s also a haunting sense that no one means what they say. Even the plot’s background layers are irritants, pinned precisely to incite a familiar, anxious itch: Jonah, the hangdog poet who lingers around Samantha, writes prolifically to the point that “it’s … a bit scary because I can’t stop.” And then there’s the Lion, her handsome male thesis advisor, who stops speaking to her altogether after months of friendliness—possibly because of a drunken night that Samantha can’t quite remember. With its references to Carrie, Heathers, and mythological monsters, Bunny is a gleeful literary horror that works popular tropes almost as if it were tapped into an algorithm. It hits all the melancholy, gossipy, bloody, tongue-in-cheek notes we expect from a cult classic, while working to maintain its self referential intelligence. If there’s a cost to this relentless satire, it might come in the form of some much-needed sincerity. And yet Bunny won me over repeatedly in its three hundred pages—it’s simply impossible to resist.

—From CNQ 105 (Fall 2019)

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!