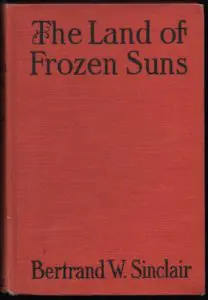

Bertrand W. Sinclair

Chicago: Donohue, 1910

309 pages

A Scottish transplant by way of the United States, Bertrand W. Sinclair wasn’t Canada’s most prolific pulp magazine writer; I know of 294 appearances, which is nowhere near the fifteen hundred or so (I lost count) logged by Ontarian H. Bedford-Jones. Sinclair isn’t our best-known pulp writer, either; that title belongs to Thomas P. Kelley, author of The Black Donnellys, Vengeance of the Donnellys, I Found Cleopatra, and, of course, The Gorilla’s Daughter.

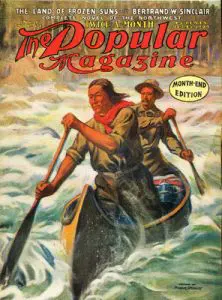

Sinclair’s distinction rests in being our best pulp writer. Though his plots are invariably marred by melodrama—a prerequisite in pulps—he usually brought something to his stories that shook convention. My favourite Sinclair novel is The Hidden Places. Serialized in The Popular Magazine (Oct 7–Nov 20, 1921), it concerns a disfigured war veteran who seeks sanctuary on the remote BC coast from Vancouverites disgusted by his appearance. By great coincidence, he finds his nearest neighbour is his wife, who believes he’d died in battle. She is now married to another man.

As I say, melodrama.

But within the confines imposed by The Popular Magazine and other pulps, Sinclair found space to write of the ill treatment of Great War veterans.

With the unknowing wife, he also presented one of Canadian literature’s most complex and interesting characters of the twenties. She’s a sympathetic figure who struggles to control a strong sexual appetite yet remains faithful to her second husband.

The Land of Frozen Suns isn’t nearly so daring, though it too pushes boundaries. Published in its entirely in the October 15, 1909 edition of The Popular Magazine, it owes something to Jack London’s The Sea-Wolf (1904), which in turn owed something to Kipling’s Captains Courageous (1897). In all three books, a well-to-do youth is saved from drowning only to find himself a captive, forced to serve on a ship as an unpaid labourer.

In The Land of Frozen Suns, the unpaid labourer is twenty-year-old Bob Sumner. The event that sets everything in motion is the drowning of his slow-talking, easy-going papa on his Texas cattle ranch. Bob’s not much like his father in that he’s a city boy—that city being St. Louis—but that doesn’t mean he’s not keen to take over the operation. However, on the very evening of his departure for Texas, he loses his billfold, pocket watch, suit, and shoes to a pair of muggers on the city wharf. When their work is done, a near-naked Bob is tossed into the Mississippi, where he very nearly meets an end similar to that of dear papa.

In The Land of Frozen Suns, the unpaid labourer is twenty-year-old Bob Sumner. The event that sets everything in motion is the drowning of his slow-talking, easy-going papa on his Texas cattle ranch. Bob’s not much like his father in that he’s a city boy—that city being St. Louis—but that doesn’t mean he’s not keen to take over the operation. However, on the very evening of his departure for Texas, he loses his billfold, pocket watch, suit, and shoes to a pair of muggers on the city wharf. When their work is done, a near-naked Bob is tossed into the Mississippi, where he very nearly meets an end similar to that of dear papa.

After a real struggle, he has the good fortune to be pulled out of the drink by a passing steamer. Bob’s gratitude ends abruptly when he realizes he’s been shanghaied. He’s allowed ashore on occasion, but a violent brute of a crewman named Tupper blocks all chances at escape. Things reach a head—apologies in advance for the pun—when the two go after each other in a frontier-town saloon:

I can feel it yet, the fierce pain and the horrible fear that overtook me when he jabbed at my eyeball. I don’t know how I broke his hold. I only recollect that, half-blinded, hot searing pangs shooting along my optic nerve, I found myself free of him. And as I backed away from his outstretched paws my hand, sweeping along the billiard table, met and closed upon a hard, round object. With all the strength that was in me I flung it straight at his head. He went to the floor with a neat, circular depression in his forehead, just over the left eye.

There was a hush in the saloon. One of the cattlemen stooped over him.

“Sangre de Cristo!” he laughed. “A billiard ball sure beats a six-shooter for quick action. I’ll bet he was dead when he hit the floor.”

Bob is finally free, but knows that in order to stay that way he must evade American law by escaping to Canada.

Bob is finally free, but knows that in order to stay that way he must evade American law by escaping to Canada.

The Popular Magazine, a chief source of income for Sinclair, encouraged stories with “North West stuff.” In having his hero cross the border, Sinclair forces Bob onto more lucrative and familiar ground.

Our hero has barely entered Canada before he’s swept up in a North-West Mounted Police raid on liquor traffickers. Bob is sprung from prison by a character known as Slowfoot George. This man, whose legal name is George Brown, has a stake in a fur-trading operation that may or may not be legal—knowledge gleaned from my grade 10 Canadian history classes has dimmed, and the Royal Charter of 1670 concerning the “Governor and Company of Adventurers of England trading into Hudson’s Bay” isn’t so much as mentioned.

The Hudson’s Bay Company, not Tupper, is by far the novel’s greatest villain. Company men intimidate, threaten, and murder rival fur traders. That Sinclair’s novel included these elements leads me to wonder whether The Popular Magazine, and the other Americans who published the story in book form, knew that the Hudson’s Bay Company was real. Because I don’t much care for HBC, and am pretty ambivalent about every character in the novel, Bob included, the passages that got me where the ones in which the company men shoot and poison dogs.

The Hudson’s Bay Company kills dogs.

Bastards.

Trivia: The Popular Magazine gave the novel its title. Sinclair’s The Trouble Trail first appears in this passage:

The river boat on which I’d taken passage was due to leave at midnight. And that midnight departure was what started one Bob Sumner up the Trouble Trail. It isn’t known by that name; it doesn’t show on any map that ever I saw; but the man who doesn’t have to travel it some time in his career well, he’s in luck. Or perhaps one should reason by the reverse process. I daresay it all depends on the point of view.

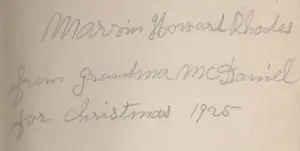

Object: A cheaply produced book bound in red boards with three plates by D.C. Hutchinson. My copy was purchased last October from an American bookseller. Price: US $6.98. It appears to have been a Christmas gift to a child named Marion Howard Rhodes.

Access: Fourteen of our university libraries have copies, as does Library and Archives Canada. Nine copies are currently listed for sale online, the cheapest being a jacket-less Donohue edition at US $5.98. The one to buy is a blue-bound Donohue in “Poor” dust jacket at US $10 offered by a Tennessee bookseller.

Access: Fourteen of our university libraries have copies, as does Library and Archives Canada. Nine copies are currently listed for sale online, the cheapest being a jacket-less Donohue edition at US $5.98. The one to buy is a blue-bound Donohue in “Poor” dust jacket at US $10 offered by a Tennessee bookseller.

The novel can be read online here courtesy of the good folks at the Internet Archive.

—A CNQ Web Exclusive, February 2018