A response to John Metcalf’s “The Worst Truth”

by John Metcalf

Biblioasis, 61 pages

Maybe I am the wrong person to write this, bored and incensed in equal measure by John Metcalf’s The Worst Truth, queer and disabled, nonbinary, enmeshed in the identity politics he is so worried about—someone too young to give a fuck about Morley Callaghan, someone who thinks the best two books that Mordecai Richler ever wrote were Jacob Two-Two and his tiny book on snooker.

I am someone who thinks that Atwood is better when she’s bitchy, that her best novel is the The Robber Bride because it’s about gossip, and gossip is secretly literature. Or I get frustrated that people like Peter Watts or William Gibson are never up for the Giller—what could be more Canadian than anxiety about the end of the world, marked by ennui, material fetishism, a genuine blankness? Maybe the only more Canadian thing would be the mark of violence, and how it intersects with sex. This might be the great Canadian theme, one that Metcalf refuses to recognize.

There are a dozen competing Canadas. There is also an argument that Canada does not exist, that the nation state only exists in a set of relationships, that these relationships are fraught. Metcalf would likely argue that I am engaging in questions of identity politics. Of course, canonizing white men, being unnecessarily harsh to white women, and mostly ignoring people of colour (he doesn’t mention Dionne Brand, Althea Price, Sam Selvon, Pamela Mordecai, Richard Wagamese, Drew Hayden Taylor, Thomas King, or Maria Campbell), is also a kind of identity politics—a gatekeeping which allows for only one kind of inquiry, and shuts off anything nasty or funny or complex.

Metcalf’s obsession with clean text extends the New Criticism ideal of writing that can be pure, the idea that good writing can be surgically extracted out of social contexts. This is a misunderstanding of how surgery works. He sees the operating chamber before and after the procedure, but does not see how the viscera has been contained. The critic André Forget makes this point in his essay on Metcalf’s most notable act of canon-making, The Century List: “by treating the short story as a purely aesthetic object, Metcalf severs the beauty of prose from the profundity of what it communicates.” He also notes that Metcalf’s list is incoherent, and filled with people that Metcalf had a professional relationship with—including someone everyone can agree with, Munro.

Thinking of the masters of the field, maybe Canadian literature is more like Munro’s “Dimensions.” In that story a woman’s husband kills her three children. Much as she tries, she cannot escape the violence. She leaves town, changes her appearance, gets a new job as a chambermaid at a Comfort Inn. The cleaning of other people’s spaces does not make her inner spaces any cleaner.

Or maybe it is like the Atwood story “Hairball,” where a chic woman with a chic life in chic Toronto—a woman Atwood makes sure to tell us has had two abortions—has a fibroid extracted from her uterus. The fibroid has teeth and hair, a memory of the potential of a body which never grows fully. She has it put in a jar of formaldehyde and left it on her mantle for everyone to see.

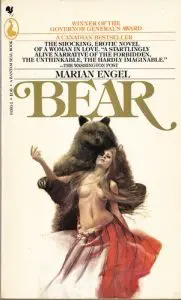

Or maybe it is like Engel’s Bear.

Metcalf is scared of Bear. He reads the story as parsimoniously as possible. It’s a tight reading, and one without potential. He doesn’t seem to understand that the novel is both an allegory and a paratext. He notes that the book was written as “a contribution to what was called the Trolley Project, a proposed anthology of pornography to be published as a fundraiser for the Writers Union of Canada. The anthology did not, thank God, materialize, but the proto-Bear metastasized.” He then goes onto to mention that Bear is a bad novel because the bear would never fuck Lou, because Lou would have smelled wrong.

by Marian Engel

McClelland & Stewart

141 pages

In these two sentences is the core problem of Metcalf’s argument. First, the bear is very much a real bear. Engel is masterful in describing the bear’s physical body, his size, and the pleasure that this size can bring—“‘Bear, bear,’ she whispered, playing with his ears. The tongue that was muscular but also capable of lengthening itself like an eel found all her secret places. And like no human being she had ever known it persevered in her pleasure. When she came, she whimpered, and the bear licked away her tears.”

The bear is also a symbol for knowledge. The book takes place in an octagonal house on an island in Northern Ontario. Lou spends her time making sense of the island’s knowledge—of Indigenous people (this is where it gets problematic), white settlers, herself, and also nature, in the form of the bear.

She is on that island as a research assistant, to learn about the archive the scientist who designed the house left behind, but the archive is destabilized via the “musk and shit” of an actual bear; the body of the bear reintegrates the body of Lou. The book is about systems of knowledge, about how to know oneself but also one’s community; it is a story about the wilderness, where the taming of the wilderness is viewed as both a complete task and a failed experiment. Metcalf does not consider that the central crisis of Canadian Literature is its continued colonialist baggage. Bear does that.

Engel never denied that Bear was a pornographic novel. Metcalf, at his pearl-clutching best, suggests that sex cannot imbue knowledge—or maybe just sex written about women, by women. He does not seem to have a problem with the boyish, masturbatory sex found in Duddy Kravitz, but the idea that our Canadian Literature could be founded on a pornographic text is a horror. Pornography is a grasping, ambivalent, difficult genre, a genre of ideas and a genre against other kinds of reading. Canada, caught between empires, never sure what it is, ambivalent and floating, might be pornographic. (Ballard, when talking about Cronenberg’s adaptation of Crash, said that Toronto was the story’s perfect setting because of the Gardiner Expressway’s eroticized blankness.)

Every so often, someone discovers Bear again (even though it won the Governor’s General Award in 1977!) and writes a difficult and trenchant essay about it. Recently, in the London Review of Books, Patricia Lockwood described the cover of the Seal edition “where the body of a softcore librarian is completely laid open to us, surrounded by flowing silk. Her tits are perfect, like two drawers of a card catalogue. The bear of the title looms over her shoulders—a Muppet designed to be sexual, smiling inside the dark cavern of his face and presumably doing her from behind.”

The novel continues to be passed hand to hand, as sort of pulp and sort of literature. (See, for example, the lurid removal of limbs in Mrs Mike by Benedict and Nancy Freedman; or think about Leonard Cohen’s paeans to Roman Catholic cunnilingus in Beautiful Losers, or the sudden way violence disrupts in domestic spaces as written by Munro; or Lynn Crosbie’s Paul’s Case or the plays of Sky Gilbert or Brad Fraser or Michel Tremblay, or, in film, anything by Bruce La Bruce or Jean-Marc Vallée.)

Bear is too pornographic for Metcalf, but he also doesn’t like Ann-Marie MacDonald’s high gothic Fall on Your Knees. He thinks it’s too lurid, that it doesn’t reflect reality. In doing so, Metcalf fails to recognize the gothic as a tradition. It might be useful to read MacDonald in the context of Matthew Lewis’ The Monk or Coleridge’s Christabel. Of course it’s not high realism; gothic novels are strange and lurid by design. MacDonald’s plotting does some major fucking damage to the dry, realist obsession of previous Canadian literature by working paratextually: it is a thing and a commentary of the thing. Barbara Gowdy’s “We So Seldom Look on Love” is heartbreaking for a similar reason: it understands taboos and how to break them.

The moment where the fibroid is removed from the body politic and placed on display; the moment where the cleaning of the hotel rooms ceases, where the distance from the material can no longer be thought to be real. Canon-makers spend a lot of time and effort considering the edges of their genre—something that breaks past, contaminates. The creation of a canon is a creation of a pure object, and the pure object must not be soiled.

Metcalf hints that he doesn’t believe biography should be part of criticism. It’s part of the concern he has with new writers, and something that he notes when he talks about who wins the Giller or the other big prizes. He can sound like Harold Bloom, who thought that women (even women like Munro or Laurence) or people of colour or queer folks did not have worthwhile things to say.

Metcalf does not recognize a variety of realisms, and a refusal of realism. There is this sense, that he would prefer (to use American examples), for literature to retain a kind of stern, observational quality—like Cheever or Updike. Other realisms, other ways of seeing, are parceled out into anxiety about identity. It’s not that anxiety of identity doesn’t exist—but there are counter readings and counter traditions that do exist. Openness to the grotesque is one kind of reading; the absorption of other stories and other people telling them is another. Fear of the other marrs Metcalf’s timid readings of sometimes timid texts.

Let’s be brave. Let’s found a (post)national literature on the novel about a woman fucking a bear. Let’s leave the fibroid in a jar on the kitchen table. Let’s recognize that we cannot move from the house where great violence has been done.

—A CNQ Web Exclusive, October 2022

Steacy Easton first read Bear on a Greyhound bus, going to Olds for a family Christmas. Nothing explains their aesthetics more.

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!