If the Quebec publishing house Editions Police-Journal is remembered at all today, it is for the hundreds of thin, pocket-sized booklets of crime, romance, and adventure fiction it published between the mid-1940s and the mid-1960s. Their output included several long-lasting series focused on Quebecois fighting crime and evil, like Albert O’Brien, the “detective national des Canadiens français,” or Sergent Colette, “l’As Femme Détective Canadienne Française.” The publisher’s most famous character was L’Agent IXE-13, a Quebec secret agent who would become a campy cult figure to those involved in Quebec’s late 1960s pop art scene. Pierre Dagneault, who wrote at least 375 of these short novels under the pen name Pierre Saurel, is said to be the most prolific fiction author in Quebec history. The booklets have long been a familiar sight at Quebec flea markets, where their lurid, colourful covers quickly attract the eye.

The publication that gave its name to Editions Police-Journal, however, was a very different kind of product. Police Journal was a cheap-looking crime sheet of sixteen pages published weekly, on pale newsprint, from January 10, 1942, to December 18, 1954. It sold for a nickel until 1948, when the price climbed to seven cents (and then, in 1952, to a dime.) Despite its title, Police Journal had no official connection to the police, and, indeed, its writers regularly accused the Montreal force of corruption and complicity with the city’s criminal elements. The Police Journal’s editor-in-chief was known merely as le Moraliste. In a practice shared by other muckraking Quebec periodicals of the time, their true identity was kept secret from readers.

The publication that gave its name to Editions Police-Journal, however, was a very different kind of product. Police Journal was a cheap-looking crime sheet of sixteen pages published weekly, on pale newsprint, from January 10, 1942, to December 18, 1954. It sold for a nickel until 1948, when the price climbed to seven cents (and then, in 1952, to a dime.) Despite its title, Police Journal had no official connection to the police, and, indeed, its writers regularly accused the Montreal force of corruption and complicity with the city’s criminal elements. The Police Journal’s editor-in-chief was known merely as le Moraliste. In a practice shared by other muckraking Quebec periodicals of the time, their true identity was kept secret from readers.

Copies of Police Journal have become hard to find. Those that have survived were usually part of the sturdier “Albums” that came out three or four times a year and gathered several issues in a single volume. I acquired a multi-year run of Police Journal (hundreds of issues) in 2019, at a Montreal vintage fair. As if he were offering drugs or other contraband, a stranger who’d heard me ask a vendor for crime magazines and had followed me for several minutes, then whispered in my ear that he had “Police Journal for sale.” Unlike the single issues that occasionally turn up on eBay, soiled and torn, these were in pristine condition and carefully arranged in chronological order, suggesting that they’d sat for many decades in a distribution warehouse.

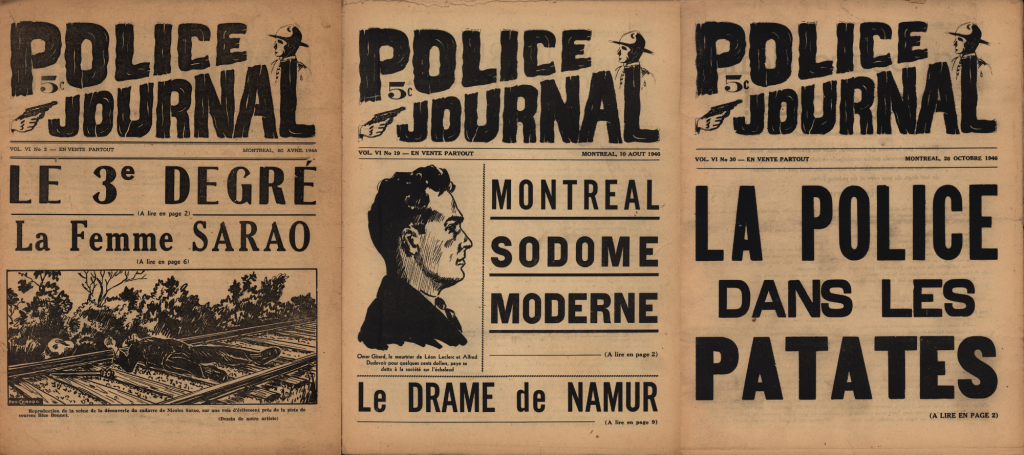

Though Police Journal was ostensibly a newspaper engaged in covering crime and vice in Montreal, it lacked the human resources—like photographers and reporters—necessary to do so in any comprehensive way. Its front pages were dominated by brief, catchy headlines in large type, like “Les Gigolos du ‘Red Light’” (March 6, 1943) or “$6,000,000 Pour Protéger Le Vice” (February 3, 1945). By the mid-1940s, small sketches or low-resolution photographs of people (criminals and politicians, mostly) began to appear on covers. Inside, however, the paper’s interior still consisted of long columns of densely packed print with no illustrations.

A typical issue of Police Journal used its front page to promise coverage of issues or events linked to the crime, vice, and reform efforts that marked Montreal’s civic life in the 1940s. The paper was especially preoccupied with the comings and goings of Pax Plante, the anti-vice crusader who’d been promoted from an innocuous clerical job at Montreal’s municipal court to chief of the city’s Morality Squad. (Named to the role in 1946, Plante was dismissed in 1948 because of political pressure.) Police Journal shared Plante’s intense hostility towards Montreal’s longstanding mayor Camillien Houde, and the province’s premier, Maurice Duplessis, seeing both as barriers to the kind of public inquiry and moral cleansing that the reform movement (which included future mayor Jean Drapeau) was pushing for.

While Police Journal claimed a moral high road, it was not averse to dangling the promise of sensational revelations as an enticement to readers. Its headlines condemned Montreal’s police force for incompetence or corruption (“La police dans les patates,” October 26, 1946); exposed homosexual behaviour on Montreal’s Mount Royal (“Les ‘Fifis’ de la montagne,” March 31, 1945); and covered unrest in Montreal’s prisons (“La révolte à Bordeaux,” November 22, 1947). In the waning days of World War II, Police Journal became obsessed by the amount of prostitution taking place in Montreal, regularly denouncing the “victory girls” (war-time sex workers known as “Les filles de la Victoire”) and their growing public visibility.

In fact, Police Journal offered little in the way of detailed reporting on any of these issues. Instead, lurid headlines led to one-page articles that interwove the barest of facts with heated commentary. The rest of each issue largely consisted of material bearing little relationship to timely crime reporting. Throughout the publication’s history, fictional stories filled at least half of each issue, and it was the success of these stories, apparently, that led the publisher, in the mid-1940s, to begin separate publication of the romans en fascicule (novellas in booklet form) for which Editions Police-Journal is now remembered.

Other content in Police Journal included multi-part series on famous crimes of the past, like the Lindbergh baby kidnapping of the 1930s, or the 1920s murder of young Blanche Garneau that led to political upheaval in Quebec. These features were obviously reworked from previously published accounts, and might run over several issues of Police Journal. With its bare-bones reporting on current crimes, its high percentage of fictional content, and its endless recycling of archival material, Police Journal could survive with no real reporters on staff.

It is through its headlines that Police Journal leaves us with a running guide to the key issues and events punctuating public life in Montreal in the 1940s and early 1950s. In these brief phrases we find reference to charity rackets, unscrupulous landlords, fixed boxing matches, sexuality in the theatre, slot machines, price-gouging grocery stores, and the spread of “blind pigs” (speakeasies). Together, these concerns reveal Police Journal’s populism—one that was both radical (in its fixation on forces keeping the average Montrealer poor and miserable) and conservative (in its horror at the immorality of Montreal theatre, or the supposed spread of homosexuality among the city’s youth).

Police Journal ceased publication in December of 1954. For almost two years, it had faced competition from the new weekly Allo Police (launched in February 1953), whose higher production values and professional reporting and photography staff made it a much livelier window onto criminality in Quebec. In October 1954, the Caron Commission released its long-awaited report on vice and police corruption in Montreal, and in the same month Jean Drapeau was elected mayor of Montreal with the promise to restore civic morality. Police Journal already seemed, at this point, to have lingered around too long.

—From CNQ 109: The Crime Issue (Spring/Summer 2021)

Will Straw is Professor of Urban Media Studies in the Department of Art History and Communications Studies at McGill University. He is the author of Cyanide and Sin: Visualizing Crime in 1950s America, and of over 170 articles on music, cinema, print culture and cities. His current research focuses on night-time culture in cities.

We post only a small fraction of our content online. To get access to the best in criticism, reviews, and fiction, subscribe!